It’s the singer, not the song.

―M Jagger, K Richards

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Personally I’ve never given birth and I don’t expect to do so. For this reason I’m not one to presume to compare writing to parturition.

Personally I’ve never given birth and I don’t expect to do so. For this reason I’m not one to presume to compare writing to parturition.

A better metaphor might be that an idea for a compositional project is like a splinter distressingly lodged under a sensitive fingernail, and the writer-artist is willing and determined to go to some extremes to physically extrude it from the flesh. Of course the metaphor is incomplete, because the writer desires not simply to be rid of the nagging foreign body, but also to refine its form into some discernible and admirable semblance of artistic expression before attaching his signature and releasing it into the wild – i.e., offering it up for consideration by the ravening critics and the reading public.

We who are interested in the craft sometimes talk about the unwritten contract between the author and his reader. You know, those things which an author is forbidden to do in a story lest he poison his readership and prematurely reduce his own writing career to a pile of unredeemable debris forevermore. Characters must stay in character. No deus ex machina. Thou shalt not put the reader to sleep. And so on.

Such rules and conventions, often cited and repeated, may suggest that writing constitutes a mode of communication between the author and the readership, and indeed one encounters this claim with some frequency. Some writers will tell you that, when they’re writing, they will periodically pause to form a mental picture of some single individual for whom they’re writing. It may be a real person they know, or it may be a stylized, idealized, perfected symbolic Reader. It’s something of a mandala, a target toward which they’re aiming their word-streams like controlled bursts of artillery fire. The writer is trying to focus on speaking directly to one representative person, assuming that particularized attempt at communication will be magically generalized to a broader readership. This method appears to work well for many writers.

I myself no longer think of writing as a form of communication, however; at least, not the kind of writing which gravitates to a more essential aesthetic ideal.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not talking about some kind of flashy artsy-fartsy glittery literati nose-in-the-air auteur pretension here. I have little use or tolerance for that sort of thing. Likewise, I have no quarrel with hard-working craftsmen who labor in the medium of words, cobbling together poems, stories, novels, movies and plays that fairly win broad public acclaim and can be tracked on all the big trendy blockbuster lists. I understand and appreciate this approach to writing, but that’s not what I’m talking about either. One kind of writing is not better or worse than another kind. Different kinds of writing simply serve different purposes. I’m talking about writing that is not calculated primarily to attract and astound and captivate readers, but which aspires to an aesthetic ideal for its own sake. Writing which seeks to transcend trendy blockbuster lists.

Literary elegance, it would seem, is often – but not always – anathema to the readership which generates the trendy lists.

I don’t think a literary writer is trying to communicate with an audience. Rather, the sum total of his focus is spent on the attempt to create the most perfect word-sculpture he can. Grasping at perfection is inevitably doomed to fail, but never mind that. This is how the literary author deals with the agonizing splinter under the fingernail, or perhaps the sliver that burns with white-hot incandescence in his mind, or in his soul. He labors to transform that stinging conceptualization into a perfect artistic expression because he, constitutionally, can do no more and no less. Only by engaging in this process can he hope to extrude the concept which rankles and get it out into the world. Afterwards, by some lucky accident, the work he has produced may or may not streak up the same trendy lists which drive the commercial writers.

When the work is conceived, written and published, the author’s connection to that work is severed except in a business sense; that is, he remains identified as the author, but the work itself is now like a fallen leaf whirling in the blusterous winds of public opinion. The work has escaped his further modification and control. It’s become like any finished statue carved in marble, or like a painting, or a ceramic vase, or a commodity for sale in a department store. What he thinks of the piece is no longer paramount. He is only a single member of a wider audience henceforth. He may have been the channel through which new art entered the world, but now it is the public’s task to judge that art according to the standards of established literary tradition and the transitive, capricious mores of the time.

Do not be deceived as many readers are: the author and the art become independent entities at the moment of publication. Published works are to be judged as physical objects separate from their authors. Some knowledge of an author’s life can help us to understand the context out of which a published work arose, but the work itself must stand or fall on its own merits, and within the broader discourse of all published works. This is what art, and literature in particular, is properly about. Art is not about a cult of personality, even if many artists (nearly all popular musicians come to mind), or writers, have never properly thought the thing through.

Image may be NSFW.

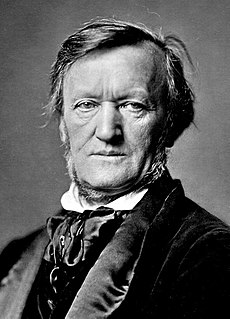

Clik here to view. Some people will not listen to the music of Richard Wagner because of his anti-Semitism. I can understand that. But it is possible, if morally thorny, to admire art while despising the artist. James Joyce presents many readers with a corresponding moral dilemma. Other artists we may judge more admirably. It’s not that the social group called “artists” or, in this case, “writers,” are not interesting themselves. Artists are among the most compelling characters any society ever produces, probably because they often have a way of giving voice to the unspoken elements comprising the shared collective unconsciousness of a society. When great artists tap into the social id and elevate that material into conscious awareness we recognize greatness because the artist is telling us something we already knew, but we hadn’t previously known we knew it.

Some people will not listen to the music of Richard Wagner because of his anti-Semitism. I can understand that. But it is possible, if morally thorny, to admire art while despising the artist. James Joyce presents many readers with a corresponding moral dilemma. Other artists we may judge more admirably. It’s not that the social group called “artists” or, in this case, “writers,” are not interesting themselves. Artists are among the most compelling characters any society ever produces, probably because they often have a way of giving voice to the unspoken elements comprising the shared collective unconsciousness of a society. When great artists tap into the social id and elevate that material into conscious awareness we recognize greatness because the artist is telling us something we already knew, but we hadn’t previously known we knew it.

But it’s always best to keep separate our opinions about art and the artists who create it. After all, the art is in the public domain and we can experience it directly, but the artist always remains a human being who is private and personal. And while we may see him in public performance, or we may read interviews with him, say, he remains a human individual whom we don’t know.

No matter how much we may love his art, he is not a personal friend. We don’t know him at all.

Tagged: art, James Joyce, Richard Wagner, Rolling Stones, writing Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.